Roger Vance is mayor of Hillsboro, Virginia. Vance can be reached at [email protected].

undefinedFor its first 268 years, the only thing under Hillsboro’s “main street,” Virginia Route 9, beside soil and rock was a small iron pipe dating to the 19th century that faithfully carried water to residents from the Short Hill Mountain’s Hill Tom Spring a half a mile north. Three culverts carved under the road helped direct deluges of storm water pouring from the mountain into North Fork Catoctin Creek. Today, under the same narrow path that was well established before 1776, is now buried the most modern of 21st century utilities, built from scratch, and to last another hundred years.

At the end of the 20th century, one of Virginia’s tiniest incorporated towns confronted some gigantic challenges. Nestled in a narrow gap of Short Hill Mountain, a foothill just east of the Blue Ridge, the historic town of Hillsboro faced a looming threat. Decaying, inadequate, and non-existent infrastructure threatened the public health and safety of the town’s 120 residents, drove down property values — in the nation’s wealthiest county — and stretched its community fabric thin.

The geography and topography of Hillsboro, where the Short Hill Mountain rises sharply on its north side and the Catoctin Creek flowing eastward to the Potomac River bounding its south side, has shaped the town’s 270-year history. High among the town’s priorities was a solution for the effective management of the millions of gallons of storm water coursing off the Short Hill, often inundating the town as it rushed to the Catoctin and eventually into the Chesapeake Bay.

Storm water management was a major element in the town’s recently completed $34-million ReThink9 traffic-calming and resilient, multi-faceted infrastructure project. Among the biggest engineering challenges presented was the management of massive volumes of storm water flowing from the steep Short Hill mountainside across Route 9 to reach outfalls into Catoctin Creek. Flooding of homes, wash out of gravel roads and drives and ponding on the highway created unsafe conditions for motorists and residents with each rainstorm.

The ReThink9 project also encompassed a brand-new sanitary sewer system, new drinking water system, undergrounding of all aerial utilities and installation of a town-owned streetlight system and fiber optic conduit to each property. Hillsboro’s first-ever comprehensive storm water management system would have to be interwoven to deconflict with miles of power and communications duct banks and their vaults, manholes and handholes, as well as miles of drinking water and sanitary sewer mains and laterals, town-owned conduit for fiber optics, and streetlight power lines.

The web of wet and dry utilities underground had to be packed within a very narrow corridor, tightly flanked by historic 18th and 19th century homes and stone walls, many within mere inches, and sometimes actually within, the right of way.

“The Hillsboro project was very unique in scope and nature,” said Matt McLaughlin, CCM, director of utility management services for CES Consulting, a member of the Volkert construction management team. “A power, telephone, and fiber optic duct bank had to be built in close relationship with domestic water, raw water, and sanitary sewer systems as well as drainage facilities. This is all located within a very narrow 24-foot roadway adjacent to historic buildings and retaining walls. It required outside-the-box thinking and extraordinarily close collaboration among the utility companies, the Volkert design engineers and the construction contractor, Archer Western.”

“Given the project’s complexity,” McLaughin added, “the town made a wise choice to use RFID and GPS advanced technologies to create a precise utility as-built plan that records, stores and retrieves data electronically for future use.”

The project began with Federal Highway demonstration funds in 2004 to study traffic calming for Virginia Route 9 in Hillsboro, which was being inundated with heavy commuter traffic from the new sprawling Washington, D.C. exurbs in nearby West Virginia and Maryland. As the average daily trips through Hillsboro was climbing toward 17,000, roadway “improvements” had obliterated or paved over the town’s sidewalks, permitting higher speeds and making pedestrian access hazardous or impossible. Rudimentary storm water facilities were inadequate and rarely maintained, creating hazardous conditions for motorists, eroding roadways and flooding homes during storms.

At the same time, Hillsboro’s municipal water system, gravity-fed from a spring located in the forest on the mountain high above town, was deemed to be GUDI by the Virginia Department of Health, beginning a 20-year Boil Water order for residents and requiring a consent agreement with the U.S. EPA for discontinuance of the spring. Antiquated and failing private septic systems, including some cesspools and pump and haul tanks, posed an imminent environmental and health threat, prompting years of study to develop a path toward a municipal wastewater treatment solution.

After the town pushed the project forward through its preliminary design and to its design public hearings in 2012, it languished unfunded as a Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) project. Finally, in 2016, the town independently began to assemble local funds for each element of the project and then decided to assume the management and administration of the project itself, decoupling the project from VDOT control, and launching a campaign to combine all the projects into one — to “Build it Now, Build it Once.”

The town hired Alabama-based engineering firm Volkert to bring the preliminary design to completion and take the project through required permitting, reviews and ultimately to bid. Upon their initial review, Volkert determined the storm water management proposed in the preliminary plans was not adequate, especially factoring in the volumes of storm water flowing off the mountain.

In consultation with the town, Volkert proposed a significant up-sizing of the underground storm water drainage system and the addition of three-foot-wide gutters to carry storm water into dozens of drainage inlets within the project’s seven-tenths of a mile. They recommended increasing the capacity of existing outfalls and the addition of new ones to ensure adequate flow to the Catoctin Creek.

However, before reaching that level of design, Volkert first had to design a number of storm water retention facilities that would be required by regulation to remove nutrients before discharge into the creek. Because of the compact and sensitive historic nature of the town and the unavailability of land for placement of such facilities, the town sought and qualified for the purchase of nutrient credits to allow it to build the storm water management system without retention ponds.

In addition to addressing the town’s drainage and storm water management issues, the design and construction of the proposed projects had to ensure ‘no-rise’ on base flood elevation of the Catoctin Creek within the designated floodplain.

“We developed a detailed study to investigate the impact of the project on the floodplain and provided mitigation strategies to avoid any potential impacts," Adane Bobo, PE, senior engineer with Volkert said. "The study went through a thorough review and was by Loudoun County, the state and finally by FEMA with a CLOMR process.”

This gave the community validation that properties would not be impacted by the rise of the base flood elevation while meeting state and federal regulations.

Today, this integrated underground storm water management system, comprising more than a mile of pipe and nearly 100 structures, collects millions of gallons of rainwater and runoff along the entire length of the project as well as 30 road crossings to direct it efficiently, controlling erosion and protecting the environment. Curbs and gutters and underdrains along the sidewalks and roadway safely sheet water away from travel lanes to flow into dozens of storm sewer inlets, vastly improving safety for motorists.

Hillsboro’s Vice Mayor Amy Marasco served as the project’s deputy manager and has 30 years experience in planning and executing environmental programs for government and nonprofits and is founder and president of The Nature Generation.

“We now have a sustainable storm water management system that reduces and directs runoff from the mountain and roadway, and that addresses water quality concerns,” Marasco said.

The installation of the system is just the beginning for the town, she said.

“The town is embarking upon a town-wide storm water program to educate citizens and businesses about best practices and ‘good housekeeping’ activities they can undertake to support the system and keep it healthy and functioning properly,” she said.

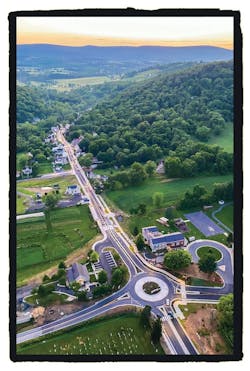

With the substantial completion of the road project in May 2021, the town has garnered wide acclaim for the success of its traffic-calming system, which includes speed and congestion-reducing roundabouts at each entrance to town, raised crosswalks and a complete sidewalk system, all built with durable and context-sensitive materials to preserve historic integrity. Along with the elimination of all aerial utilities and the planting of more than 200 native species trees and thousands of flowers and shrubs, the surface work has also been cited for enhancing the beauty of the town.

“However, what people cannot readily see is the tremendous engineering and construction work lying below the surface that will, for generations to come, ensure the health and safety of residents of this town and help protect the environment and water quality for the entire region,” Marasco said.